On Monday, June 2nd, we got a guided tour through Westminster Abbey. This historic church is the final resting place for many royals, poets, soldiers, and general people of influence. And many other figures of Britain’s past are also commemorated here, even if their bodies lie elsewhere. With this post, I’d like to cover some of these figures.

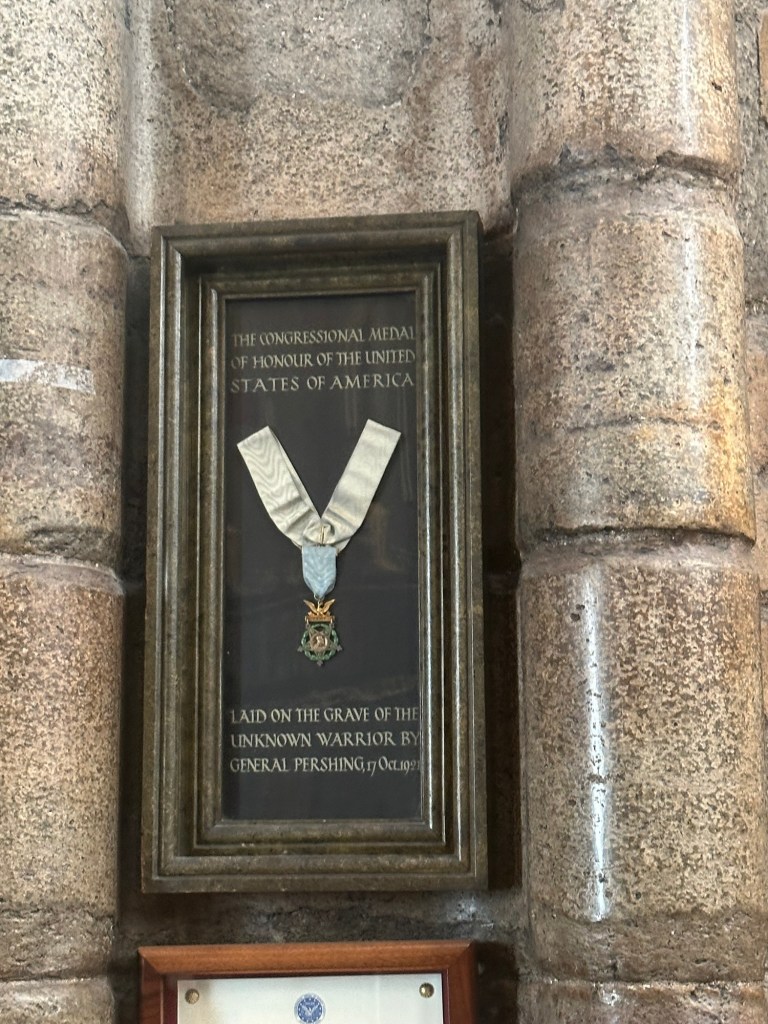

After seeing some sections of the beautiful architecture and learning a lot about the history of the building itself from our tour guide, our group’s first proper stop was at the grave of the Unknown Warrior. As is natural, nothing is directly known about this person. The body itself is that of a British soldier who “fell in the Great War 1914-1918 for King and Country” (per the coffin plate inscription). The memorial itself is representative to the thousands of soldiers who died in war with no grave for their families to mourn at. In general, it represents the sacrifices of every soldier who died and has died in war. The idea itself came from Reverend David Railton who noticed a grave of (by the inscription) “An Unknown British Soldier” in France. He then started the process that ended with an unknown warrior being buried and the memorial being made. Many ceremonies and items have been made or added to commemorate this memorial. The picture above is the bell of H.M.S Verdun which is the ship that brought the body from France. The other is a Congressional Medal of Honor from the United States of America awarded to the warrior on October 17th, 1921. Under that, not visible in the picture, is a flag from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society given in October 2013. Standing in front of this memorial was, in itself, a powerful experience. With all it represents, it was an honor to be in its presence.

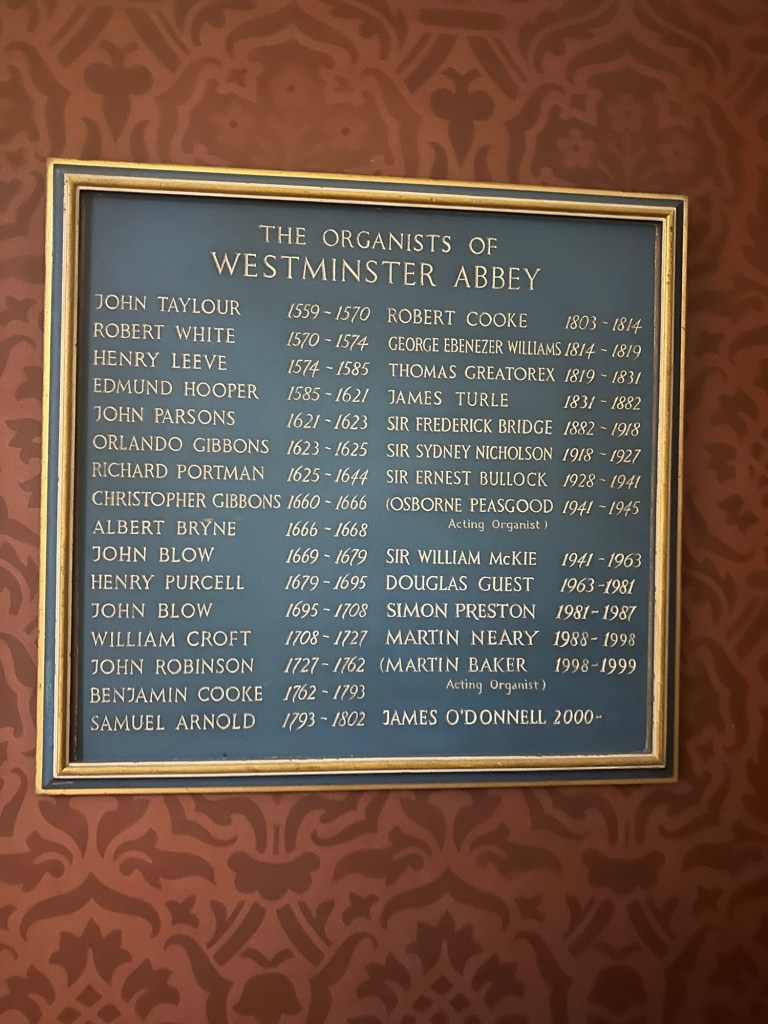

Before explaining the memorial of one man honored in the Abbey, I’d like to explain the item related to him that caught my attention, the Abbey’s organ. Of course, the building is a church and still holds service to this day. Still this church’s organ and its history is quite a marvel in itself. Now, the organ in the picture, The Queen’s Organ, was only made and installed in November 2013. However, there is evidence of organs in the Abbey all the way back in 1304. The main artifact of those older organs are the pipes of the Harrison & Harrison organ. In the distance of the roof picture above, you can see part of the piping for the instrument. Although only installed in 1937, it uses the piping of one of the last manual organs built in 1848. The main other specific history of organ use is through the records kept of the Abbey’s organist from 1559 to now. Some organists only served for a few years, some for ten to twenty, but organist James Turle served for 51 years, from 1831 to 1882. When there, I did not think to take a picture, but Turle has both a monument and a memorial window in the Abbey. Turle was born 1802 and his death in 1882 also marked his retirement from being the Abbey’s organist. From the age of 8, he worked at the Abbey, being deputy to the current organist, Thomas Greatorex. He of course took over as organist and Master of the Choristers when Greatorex died. Burial at the Abbey was offered to Turle before his death. He declined, wanting to be buried with his wife at Norwood cemetery. To be able to keep a job like this for 50 years, until your death, is commendable.

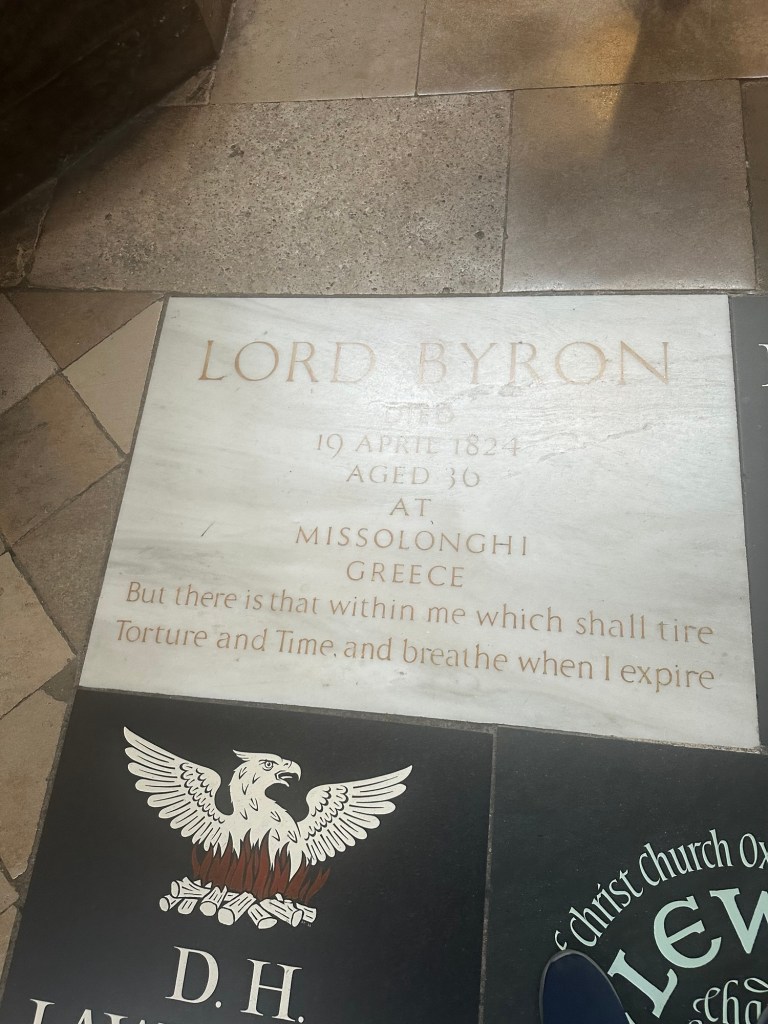

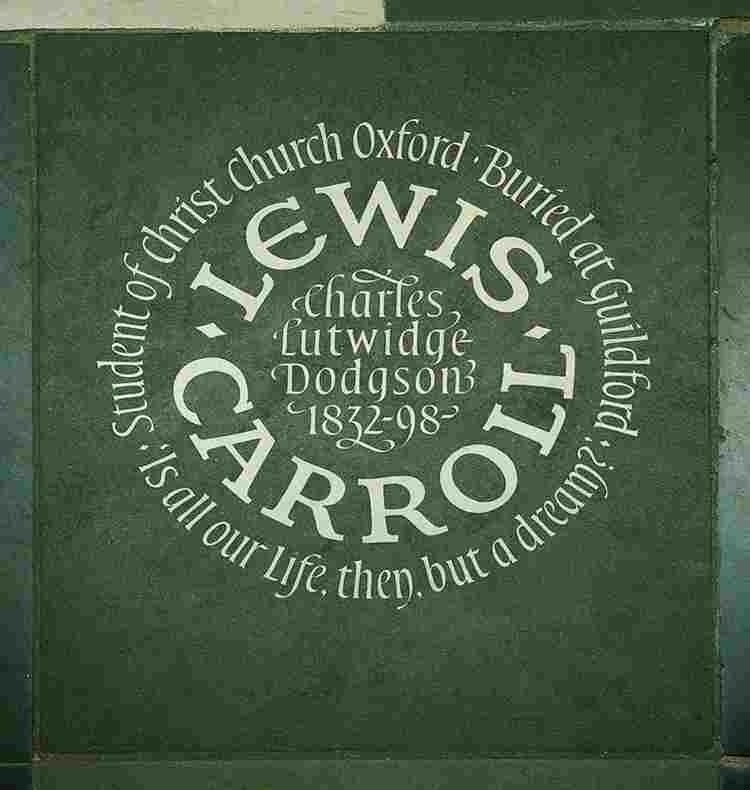

With some of my last words in this blog, I’d like to do a bit of an amuse-bouche of a section I could have written this whole post about: Poets’ Corner. The first is English poet Lord Byron (1788-1824). Byron was a major player in the Romantic movement and is seen as one of Britain’s greatest poets. I personally read a lot of his work in high school and find the crazy history of his life along with the influence his poetry had makes him quite the interesting figure. The second figure is one I actually did not get a picture of while at the Abbey. Though, you can see my foot on it in the picture of Lord Byron, I had to get my picture of Lewis Carroll’s memorial from the inter-webs. Carroll (1832-1898) is a name most will recognize for his works involving Alice and the Wonderland she often travels in. Carroll, non-pseudonym name being Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, in his early life was a mathematical lecturer at Christ Church in Oxford. There is a famous tale of his taking the daughters of the church’s dean rowing on the river. There he told them the story that would eventually be published at Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. I personally read a lot of Carroll’s work in my senior year of high school when adapting his stories into a play (our teacher could not get the rights to the play we wanted to perform, so I got to write it instead… woohoo!). The influence Carroll’s work has had is obvious by the number of movies and other art that has come from his nonsense stories written almost two centuries ago. Neither of the men with memorials mentioned here were buried at Westminster Abbey, though they are remembered in the church for their work, nonetheless.

I very much enjoyed our journey to Westminster Abbey. The building itself is beautiful, and I find it fascinating that so many important figures are immortalized in one place. Truly a marvel.

Squirt was a bit overwhelmed by the Abbey. The idea of death makes him just a bit queasy, and so, I don’t have many pictures of him to share today. Similarly, I forgot to take any pictures at the play we watched the night of our visit to Westminster Abbey, a play called “1526.” It was absolutely phenomenal, very powerful, and definitely one of Squirt’s favorites!