Today was our last museum day here in London, and we finished strong with the Victoria and Albert Museum! While I have been there before, I figured the exhibits have changed some since then, so I was exited to see it again.

The tube ride from the Russel Square stop to South Kensington was cramped and unfortunately long, and, in the interest of saving battery on my phone, I could not entertain myself with anything other than my imagination and passive listening. Overhearing Grason and Isaac talk about the things they saw and did during our stay gave me some regrets that I did not feel before then. I could have revisited certain museums, I could have bought tickets to more extra shows; I hope that I will not look back on this trip with that mindset. I accomplished much of what I set out to do, and between events being cancelled and being laid up by Covid, some of the chances I could have seized disappeared without any fault of my own. I have done a lot of new things, and gained new experiences, and I am proud and happy in those facts.

Anyway, back to the museum!

Getting to the Theatre and Performance section would have been difficult without Shawn’s knowledge of the floor plan, accrued through his several visits over the years of leading this program, I would wager. Once we all gathered at the entry of that section, we all, in typical fashion, began to absorb its contents at our pace; at the very least, I did. The first portion, closest to the entrance, consisted of costumes, photographs, and other memorabilia across the history of the Royal Academy of Dance. Dancing is a performing art that I have never gotten into at anything past the surface level; it is subsequently my weakest skill of my performer’s triangle (the other two skills being acting and singing). But I still appreciate the physical strain and full-body dexterity required to dance at a high level, let alone a decent one. I caught snippets of history about the Academy, and its timeline allowed me to better arrange in my brain the movements involved in furthering dance as a career with genuine merit, and make some inferences about the timing of similar movements in theatre.

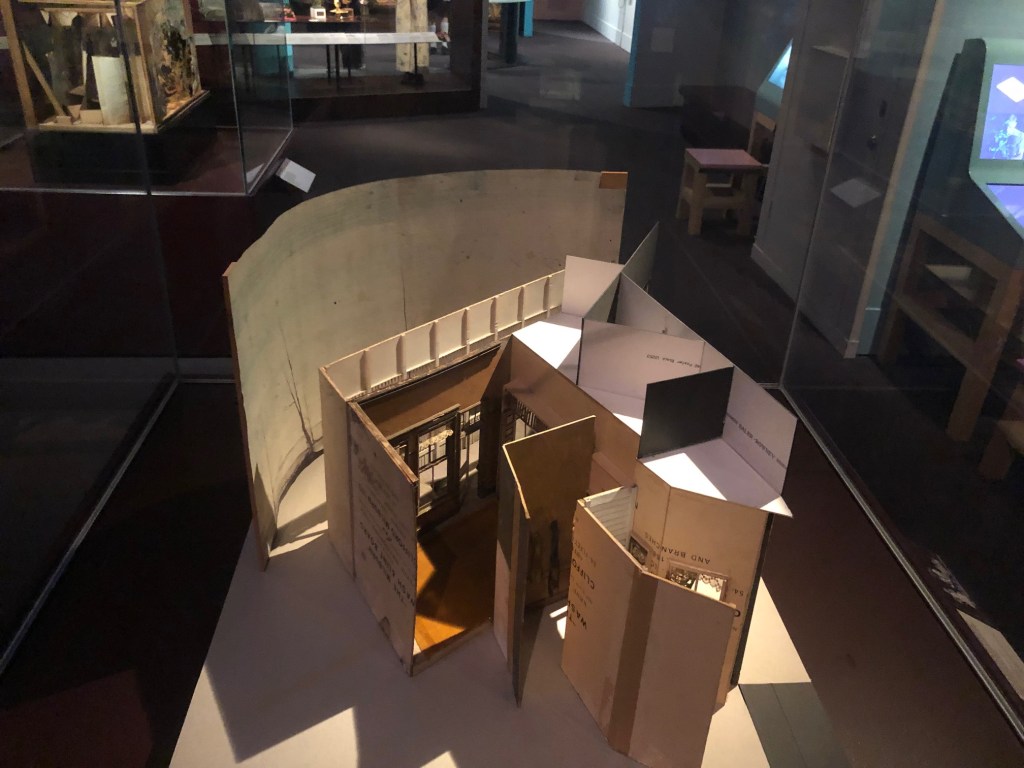

From there onward, the exhibits covered English forms of performance (drama, film, music, circuses, etc.), with the majority of the portions covering one aspect of theatre. There was a significant costume section, another dedicated to set designs, an interactive booth for sound design and projections respectively, and others, all of which featured very famous artifacts or represented works done in the creation of famous works. While the other portions awed me or occupied my attention for a brief while, my favorite pieces were those exemplifying set and costume design in particular. Something about the sketches and renderings and scale models involved in set design, and the simple or deeply detailed representations created in costume designs, makes one feel like a grand creator, bringing beings or worlds to life with scale rules, paint sets, and cardboard (all of the set models were made out of better materials than foam core board or card stock, but the materials used do not change the feeling).

One particular model stood out to me, not because it was cerebral or revolutionary or made with unusual materials, but because I have a personal attachment to the playwright of the play the model was made for. It was a fully colored and detailed scale model used for the 1971 production of Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey into Night performed by the National Theatre Company. One of my first truly good monologues that I found and prepared myself is said by the character Don Parritt in O’Neill’s play The Iceman Cometh, and my Theatre History II course with Morgan Hicks gave me more of his background information and his impact on American theatre as a whole. I must confess that I have never read Long Day’s Journey into Night all the way through, but I know enough about it to know that it is very similar to two of the required readings for this summer course: The Corn is Green and The Glass Menagerie. All three of these plays are semi-autobiographical, reflecting on the playwrights’ circumstances during their childhoods or young adulthoods All three of them follow young men as the primary characters as they navigate the barriers to their freedom; those being family for Night and Menagerie, and upbringing in a mining community for Green. Finally, all three of them, if their words are taken to the a literal extent, are set in residential spaces or homes (though how hospitable they are varies).

The Theatre and Performance section lit a creative fire in my mind, compelling me to create in the future. Unfortunately, it was so hot in that section that I would have believed it if someone told me there was an actual fire! I took my time getting everything I could out of that section, but by the end I was pretty work out, so I did not explore much of the museum after that.

After a detour where I bought some useful-looking Shakespeare books and a souvenir for a friend at the Globe Theatre’s gift shop, as well as a few hours of rest at the hotel, the group regrouped and walked over to see The Woman in Black. I knew it was supposed to be scary going in, but what I got was beyond my expectations! The way tension was built and varying levels of sound were utilized have the play an energy similar to a horror movie. The deceptively simple set allowed for some excellent shadow work, and the two actors were absolutely fantastic at slipping between their “real” selves and the characters they plaid in the haunting narrative. Like with House of Shades, I ran into an issue where certain taller shadows got cut off from view due to the balcony seating above the stalls. That aside, there was nothing I could find issue with in the production, and I would be more than happy to be involved in a staging of it later on in my lifetime.