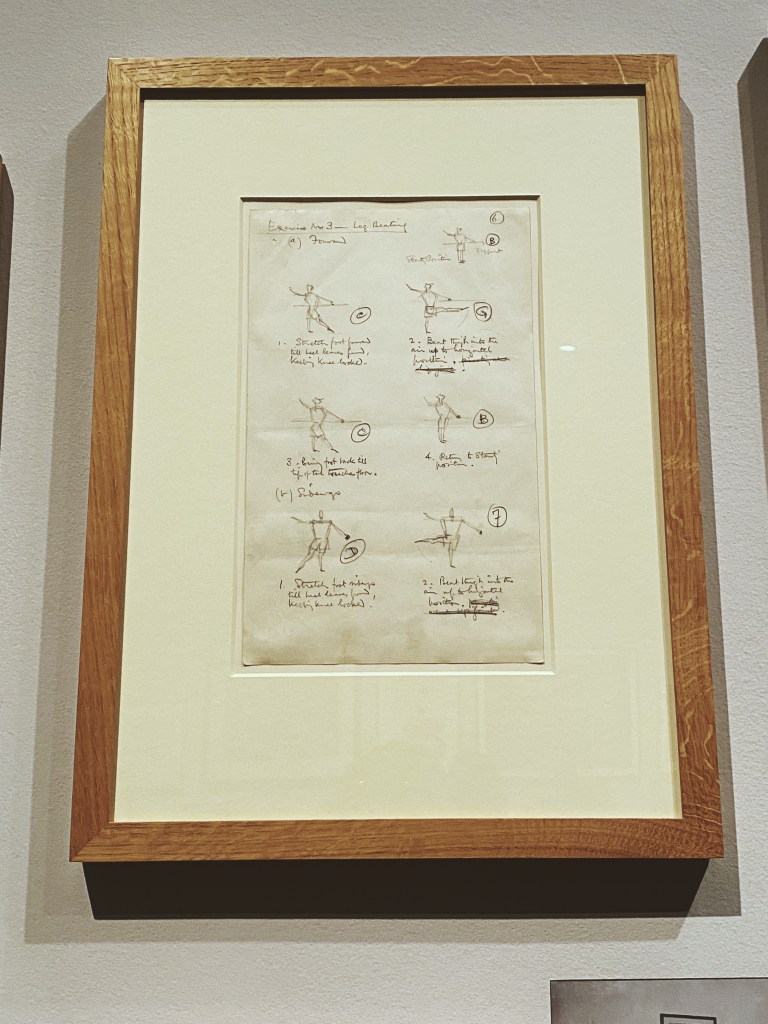

At the beginning of the Theatre and Performance section of the Victoria and Albert Museum, you’re greeted with two rooms that contain quiet relics related to ballet dance. It surprised me, honestly, that so much of the exhibit was dedicated to the study of ballet because it’s not something that I immediately associate with theatre, or at least, not as a thesis statement for a theatre exhibit. However, when walking through halls of dance costumes, I was struck by the tension of how small and fragile these dresses appear compared to the strength required of the dancers. Charts of exercises and photos of dancers in training line the walls as testaments to the years of work required to perform in this field.

As I approached a photo of Adeline Genée in The Dryad, I couldn’t help but think of Laura Wingfield. Genée stands on pointe looking back at the photographer as she lifts a tree branch towards the sky. The wall text explains that The Dryad is “the story of a nymph trapped in an oak tree and only released once every ten years…she falls in love with a shepherd and is in despair when, a decade later, she finds he has been unfaithful” (Adeline Genée in The Dryad-1915). Every ten years the nymph is set free from the home that has become her cage, but ten years is a long time to wait. If you’re confined by illness, anxiety, or fear for ten years, you miss out on a lot of life. For me, this is the essence of who Laura Wingfield is: her mental and physical disabilities paralyzed her for so long that she struggles to catch up with her peers and enter the world of the living.

Yet, seeing these costumes on display made me realize why I disliked the take on Laura that we saw at the Duke of York’s Theatre. Lizzie Annis’s rendition of Laura was much more childlike than I expected her to be, and maybe this choice was the director’s interpretation of Laura’s mental illness. However, I think what we missed from Annis’s performance was Laura’s strength. Despite the ways in which her disorder, and her inability to receive help for that disorder, slowly make her world smaller, we see glimmers of the person that she could be rise to the surface. She acts as a peacemaker between Tom and Amanda, she “notices things” like Tom’s sadness (Williams, Act I, Scene IV) and takes them to heart, and of course, she very briefly begins to open up to Jim. Her illness may make her appear fragile like the glass menagerie that she treasures, but these glimpses of happiness show us how easily Laura could come alive again, if, like working a muscle or rehearsing a dance, she was to edge into the outside world more often.

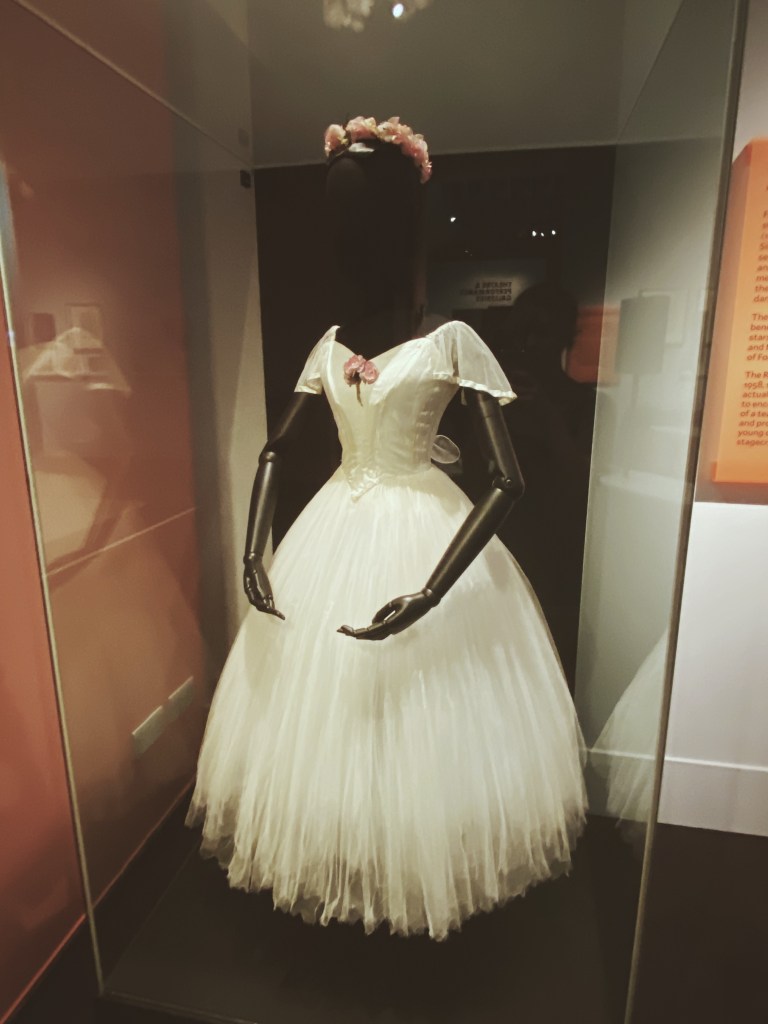

In a similar sense, the Victoria and Albert Museum’s display of Margot Fonetyn’s costume in Les Sylphides appears small and unassuming at first glance. A gauzy, white tutu with a pink flower crown and the smallest, most delicate wings sits inside a glass case near the corner of the room. It’s almost hard to believe that something so small and ethereal housed a person as strong and capable as a world class ballerina. This blend of strength and fragility is, I think, what I wanted to see from a character like Laura. Yet, Annis’s take seemed to leave little room for hope for Laura Wingfield.

After Jim kisses Laura in the Duke of York Theatre production that we saw, Annis’s Laura looked dazed and goofily happy, and the audience laughed at her naivete. A similar tone occurred as Laura argues with Amanda about opening the door for Jim and Tom. Annis shrugged as if trying to win over the audience, and again, there was a moment where they laughed at how avoidant she was. Maybe I’m being overtly critical, but I just didn’t understand the character in this way. Leaving room for a kind of pitying laughter implies that Laura exists so far away from the outside world that she’s an oddity that can never be comfortable in reality. In short, I wanted to believe that someday, even if it took another ten years after her encounter with Jim, Laura might gather enough courage to try and live again. I wanted to believe that Laura would grow to leave the apartment like Genée’s nymph continually breaks out of her tree. Jeremy Herrin’s production didn’t convince me of this. However, the Victoria and Albert museum made me realize just how possible it would have been to communicate Laura’s quiet strength even through something like costume design.

More later,

Kath

Sources

Adeline Genée in The Dryad (1915). Wall text, Theatre and Performance Exhibit, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Williams, Tennessee. The Glass Menagerie. New Directions, 1999.